Here's what happened.So I'm at home for the summer after my junior year of college. I'm working a little bit, practicing my horn (trombone) a little bit, typical low-key summer. I decide to shoot some hoops on my badly rusted childhood basketball goal. I step up to the free throw line... brick. I run get the ball and try again. Brick. I try a few more shots... mostly bricks. Wow, I didn't remember how to shoot the ball. So I decided to try an experiment. What if I work on shooting the basketball as methodically as I practice my instrument? I was at home for the summer, so I had plenty of time... and I tried it. The most awesome part is that it worked. I got really good at shooting the ball. Method to the Madness I decided to be systematic about my approach to shooting the basketball. Just like practicing the trombone, I started with something I knew I could do every time. For playing my horn, its a nice concert F in the middle of the horn. For shooting a basketball, it's standing two feet in front of the goal. When warming up on my trombone, I don't move onward until I'm solid on the easy stuff.. then I start to stretch the range and technique. I did the same systematic approach on the court. And it worked beautifully. So let's talk about the brain for a second. All skill based activities deal with synaptic connections in the brain (aka muscle memory). Once you perform a new technique, your brain creates a synapse, or pathway. When you repeat, it reinforces that synapse. It's kind of like if you walk over the same patch of grass every day for a few weeks.. the path is nothing at first, but eventually it becomes ingrained. Now, if you took a slightly different path each time, the grass wouldn't be as affected. So it is important to make sure it is exactly the same every time. I figured out how to coordinate my body to make the shot. Then I repeated the motion over and over and over and over. You get the idea. I was slow and methodical. If I missed a shot, I would examine the technique. Then I would shoot the ball a hundred more times (sometimes literally). Here's the system I set up (from what I can remember of it):

Story on the side! So my basketball shooting got really good! It lasted too. Well into the next school year. I would go to the basketball courts and continue my shooting practice from time to time. One time a bunch of athletes came out to play a game. I'm pretty sure they were football players and they were huge. They couldn't really kick me off the court, so I was invited to play. They were way better at ball handling than I was. They were also in better shape. Which is why it was so darn fun to NOT miss my shots when I got the ball. Especially the 3 pointers. There's nothing like a skinny little trombone player holding his own with some real-deal athletes. I had the time of my life. Complicated Stuff - The Mental GameNow it's time to get into the other part of the method that's not so straight-forward. There's been numerous books and articles written about this method in every field. This part is the mental game you have to play in order to fine-tune a skill. I call it "zooming out." To me, I mentally zoom out of the situation and let my physical motion go on auto pilot. When I was shooting my bazillion shots, I would zoom out further on each repetition. As a musician, I like to focus on my breathing. It brings me the most calm (especially to my mind). Here's my process:

Good Luck In my first few years of teaching, I was afforded the opportunity to put this theory to practice.

0 Comments

Some thoughts on teaching rhythm...I was creating some extra counting resources and thought I'd muse a bit on how I like to do things. Specifically, I was working my new set of progressive rhythmic reading (Count. Play. Level Up.). I even found a nice old-school "video game" font to use. You can find the sets in the Sight-Reading Section. I've broken it into a few strategies that I've always found to work. So here goes.. Vocalising the CountsI've always found it beneficial to make the students count out loud when first working on an exercise. This forces the students to think numbers (connecting numbers to beats) as they count. It also helps them keep their eyes on the correct beat. At first, we just count. Students should imitate the music with their voice as much as possible. For example, if you have a whole note, have them connect the numbers with their voice-OOOOOONE - TWOOOOOO - THREEEEEEEE - FOOOOOOOUR. My thought is that if you can't say the counts correctly (especially in easier music), you probably can't play it correctly.

In the end...

First and Most Important - How Does Your Band Sound?

Style and Literature Selection  Style is always one of my favorite areas in which to work. This is where you get into teaching music, as opposed to just teaching the mechanics of playing. Now.. this is largely my opinion, but here's how I've come to see a great festival program: 1) March - Always play a march (my opinion).. it's our history. Articulations - on the firm "tah" or "too" side (as long as it's not a legato melody) Note Lengths - slightly separated throughout, notes typically don't connect Balance thoughts - usually a great time to address melody vs accompaniment -- always make sure you can hear the melody!!! Percussion - Gotta hear that bass drum (paired with the basses!) 2) Ballad, Lyrical Selection - This is a great chance to show your expressive side. (Side note: For younger groups not ready for a long lyrical piece, pick one that has a lyrical section like Michael Sweeney's Celtic Air and Dance pieces). Articulations - on the softer "dah" or "doo" side Note Lengths - connected, little to no space - often rounded down on releases, don't chop off notes Phrasing - Do the dynamics on the page. Make sure students finish crescendos, etc. Then add some of your own. Teach students hairpin dynamics or how to find the peak of a phrase. Stagger Breathing - Assuming you're not one per part, stagger breathe everything. Shoot for no "holes" in the sound. Finish phrases! 3) Overture or Specific Style Piece - This is where you have the most freedom. You've shown your ability to play a classic march, as well as your expressive side. Now show you can handle some standard band literature. This is often the best chance to pick a piece students will really like.. I would recommend staying away from the pieces that are too "campy." Find something with a good melody, good harmonies, and one your band can sound great on. Musical Devices - The musical devices used will vary piece to piece. Just make sure it makes stylistic sense. Be specific. Be VERY specific. The judges should be able to tell exactly what you're playing without even looking at the score. **The most endearing comments I've had are when the judges commented on the fact they didn't even need a score based off of the clarity of performance. Other Thoughts on Literature Pick music you can sink your teeth into.. The idea is to play it to perfection. Now, don't pick really easy music, just pick something that's appropriate to work on for a while and really play well. Leave the really hard stuff for the parents on the Spring Concert :) ... I always read a LOT of music (which helps with sight-reading!!), while trying to determine a great fit for festival. Sight-Reading Read music all the time. All the time. Sight-reading everything from lines out of the book, to band pieces, to etudes, to pop tunes. I'm a huge fan of "cramming" music. It doesn't have to be perfect. Develop a System 1) Counting - have a system for counting difficult passages 2) Tizzling or Singing - have a system for students to "perform" the piece with out playing on their instruments.. You can "count" them through the music and put it together 3) FIND ONE - I always tell students to find one.. if they know where one is, the band will stay together. If they don't understand a rhythm, have them find the next beat one. As a conductor, always give a clear beat one when sight-reading. 4) Rehearsal Marks - These are EVEN BIGGER downbeats. This is where you save your band if they fall apart. Teach students to look for the next rehearsal mark if they're completely lost. PRACTICE Sight-reading. This takes time to develop the skill as a band. Don't wait. Sight-read all year long and you won't have to try and cram it in before festival. Final Thoughts Remember that festival is a wonderfully educational experience for students. Teach students how to act as professionals. Teach students how to respond to critique. Teach students the value of striving for perfection. Teach students what the professional world of music is like. Most importantly, teach students about great music, and performing it to the absolute best of their abilities.

Fundamentals for a Great Sounding Band

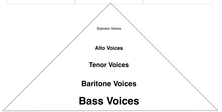

I’ve always liked what I once saw in a Bruce Pearson (Standard of Excellence series) article: A + E = T, which means, Air + Embouchure = Tone. It’s a very simple concept but will make all the difference. If a student has a good airstream alongside a proper embouchure, a good sound will be produced. Now for the specifics: Airstream There’s a wealth of materials focusing on breathing and the airstream. Search out resources for methods and exercises, try them out, and use what works for you and your group. Here’s what helped my band to sound great: 1) Posture — I always obsess about posture. I even do the “rest, ready, and play” with younger groups. It’s a visual cue that holds students accountable and as the teacher, you can constantly remind students of posture to keep them focused in rehearsal. I teach students that your lungs can work correctly if your lungs are collapsed down on themselves. 2) Steady Air — When I first started teaching, I used to talk a lot about MORE air. I later amended this to STEADY air because students tend to create a more consistent sound with steady air. A great exercise is to hold the hand in front of your face and blow a consistent airstream. I also talk a lot about keeping the stomach (core) muscles firm as to keep the airstream supported. The words “steady air” made a great leap in the sound of my early bands. Remington Long Tones (or something comparable) and steady air — every day. Embouchure Here’s where it can get really fuzzy as many people have varying views on embouchure.. I’m briefly going to give a few basics that have worked for me. Please know that I don’t see any of this as Gospel! 1) Flute — Work on the head joint a lot getting out the various partials by redirecting the air, make sure to have a tall syllable in the mouth and that aperture is focused (not too thin and not too spread) 2) Single Reeds — Get the teeth in the center of the bottom lip (I tell students they would “bite” though the middle of their bottom lip), keep the lip stretched out and the corners firm. Students tend to change their embouchure when they place the reed in their mouth, so you have to watch this as they bring the top teeth down (obviously make sure the teeth are on the top of the mouthpiece) … when articulating make sure that the embouchure isn’t affected. Using the mouthpiece only is a great habit to get into.. check the pitch. If they’re flat on the mouthpiece only, your intonation is doomed (as you can fix sharp by pulling out) 3) Brass — Make sure placement of the mouthpiece is good (look up some specific resources about each instrument’s placement, as opinions can vary greatly). I am a believer in a RELAXED brass embouchure. Corners should be tight, but the middle should not. The air should produce the note. I say this a lot: “The AIR should produce the tone.” Meaning there is a steady and consistent airflow to create that starts and sustains the sound. Buzz on the mouthpiece a lot and learn what a good buzz sounds like. Do sirens, scales, etc. Have the woodwinds play lines out of the book while the brass buzz them. For high notes, focus on the direction of the airstream and the speed of the air. Squeezing lips will produce a higher tone, but if they get in this habit of squeezing, they’ll have a very difficult time fixing it in later years. In Closing Here’s the takeaway. Students must have a characteristic tone. If every student plays with a characteristic tone (emphasis on young bands at the moment), then you’ll have a good band. Instrumentation matters, balance, blend, all that stuff matter… but if the kids don’t sound good individually, your band won’t sound good. There are ways to hide in numbers and such… don’t do that, just make the individuals sound good and you’re set. **Note: the above opinions have worked for me. I’ve done most of my teaching in places that there are some students who take lessons, most do not. I always had mixed classes of instruments, so these are what I used to find success.** Good luck! Warming up is an important of any music (especially wind players) rehearsal. An effective warm up should address the physical aspect of preparation, as well as the mental aspect. There's an enormous amount of great warm-up sets out there and I thought I'd offer some personal thoughts about how to effectively use all the different resources at one's arsenal. Tone Quality I think that practically every band director would agree that tone quality is the most important element of playing. As I tell my students all the time, you can play some music that is incredibly difficult and challenging, but if you don't sound good, it's not impressive. Bands need to sound good to be successful. So, after some breathing exercises to get the air going, long tones should be incorporated. A focused airstream is essential to great tone production. I prefer Remington's way of descending chromatics, but really any sustained pitches in a comfortable range will do. During these long tone exercises, students can really focus on air and embouchure. I won't go into specifics about embouchure and such, as there are a TON of great resources out there. For woodwinds, you can always refer to the Westphal (Teaching Woodwinds). For marching band brass, I would take a look at what a lot of the drum corps are doing... since brass embouchure is what they do all summer long. I also like how a lot of them focus on keeping the embouchure healthy (always remember to warm down!!!) As we all know, without a solid foundation in tone quality, blend and intonation are not really a possibility. You could probably play with a "balanced" sound, but it wouldn't be a good sound.. Flexibility Next would be applying that good sound while getting around the multiple registers for the instruments. For brass, this means flow studies and lip slurs. It takes a while for young brass players to master getting over the partials and centering the tone and pitch while doing so. Students must master the correct vowel placements inside the mouth and get the perfect air speed. Again, if you want to see some more in-depth exercises and explanations, check out what the drum corps are doing. I really like what Carolina Crown does to warm up and their attention to the health of their chops (note: I've seen more of what they do than the other corps because they're right up the road...the other corps probably do great stuff too!) Then comes the woodwinds. Woodwinds obviously don't need to warm up the lips like brass players do, so this is a great time for them to do some work in the various registers (and moving between registers) as well as getting the fingers going. If you use Foundations for Superior Performance, you know this well...great book. Pick your favorites and use them for a quick marching warm up if necessary. Also, if you have the directors/staff to do this, flexibility may be a good time to split the brass and woodwinds to focus on specifics of the warm-up. (but always bring them back together for final tuning and ensemble sound)  Ensemble Sound Once you've gotten the basics of the individual warm-up and playing down, then it's time to focus on the ensemble sound. Firstly, musicians should be striving for a blended sound in their section and across the band. I recently received a comment from a judge at Festival pertaining to the fact that the students played with a characteristic tone quality, so much of the intonation took care of itself. I say this because if the musicians have that characteristic tone quality, then blend should happen pretty easily, creating a rich and sonorous quality to the ensemble. Another important aspect of ensemble playing is balance. Balance refers to the volume of individuals as well as sections. In a clean ensemble sound, you don't hear individuals "sticking out" of the texture. Once sections are playing the same volume, then its time to employ the balance between the sections. The most common way to create a rich and dark ensemble sound is to employ Francis McBeth's Pyramid of Balance. There are other methods of balance out there, but I think this will probably give you the most success. Plus, Francis McBeth's music is awesome. Now, let's not forget about intonation. We've all seen tons of different ways to tune an ensemble. I'm not going to say a specific one is the best or even recommend one. You should try out various tuning methods until you find one that works well for your ensemble. What I will say though, (my opinion) students should be tuning at all times. Because the temperature is constantly changing (especially in marching band!!!!), students must constantly adjust and need fine-tuned ears to excel with intonation. You definitely don't want that "fuzzy" sound that results from out of tune playing. Playing in tune is a battle, grab your tuners and get ready for the fight. Articulation and Cleanliness It is also important to define an ensemble articulation. Though each instrument has it's own specifics for HOW to articulate, the end result of the beginning of the sound should be homogenous. Incorporate articulation exercises of all types. Then make sure that students LISTEN to proper articulation demonstration (by a director or great student player). After hearing great articulation demonstrated, students must then re-create the sound, and LISTEN to each other in order to create a consistent sound across the band. Also, write out exercises for every articulation students will see within the halftime show/stands tunes/etc. Practice these in the warm-up and apply when necessary (i.e. accents, staccatos, tenutos, etc). Note Length is also a very important aspect to address during the warm-up. Note lengths should be addressed from the first note played. This is especially applicable to releases. A great band will release together consistently...a developing band will have various individuals hanging over and releasing too soon (both bad!). You can also address style within the warm-up, especially if it is in relation to what the field show contains. Maybe there's a section where you place some space between quarter notes. Work it out in the warm-up and apply it later. In conclusion, the ensemble warm-up is one of the most important things a band will do. If you consistently warm up the ensemble before rehearsals and performances, the ensemble quality will grow in all of the above mentioned areas.

These are just some thoughts, if you read, hopefully you'll find something useful. If I left something out, add it in the comments section! |

AuthorThe musings of a composer that also band directs!! ... or maybe it's the other way around.. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

Follow on Youtube, Instagram, or Facebook

|

Tip Jar? Click below. More coffee. More free stuff.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed